By Debby Lim (Dentons Rodyk)

With effect from 29 January 2026, Singapore has replaced the temporary COVID‑era Simplified Insolvency Programme (SIP 1.0) with a permanent framework embedded within the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act (IRDA). The revamped iteration (SIP 2.0) marks a clear transition: what began as emergency relief has now been absorbed into the core design of Singapore’s insolvency system for small and relatively straightforward cases.

This update outlines the structural shifts introduced by SIP 2.0, and considers their broader implications for how small corporate distress is expected to be addressed going forward.

Policy signal

SIP 2.0 should be read less as a technical upgrade and more as a statement of intent. It represents the latest iteration in Singapore’s ongoing effort to discipline how corporate distress is addressed at the lower end of the value spectrum—where costs, delay and misplaced optimism have historically done the greatest damage.

The policy choice embedded in SIP 2.0 is not to expand judicial discretion or introduce novel rescue tools. Instead, it is to sharpen incentives. The regime encourages companies to engage creditors early where a viable business remains, but withdraws tolerance for prolonged uncertainty once that premise becomes doubtful. In this sense, SIP 2.0 is less about facilitation and more about triage.

Three themes are apparent:

Access over formality – eligibility is determined by debt quantum and case suitability, not corporate labels;

Speed over process – routine court involvement and public advertising have been removed; and

Discipline over drift – tighter moratoria and restrictions on repeat use are intended to prevent delay‑driven outcomes

Taken together, these features signal a shift towards earlier decision‑making, lower value leakage, and clearer outcomes for small insolvency cases. It seeks to separate cases that merit a final restructuring attempt from those where an orderly and economical exit is the more rational course.

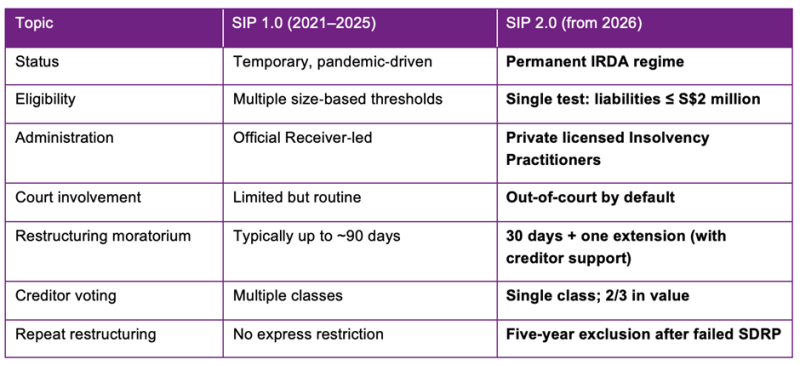

Key changes at a glance

Structural shifts under SIP 2.0

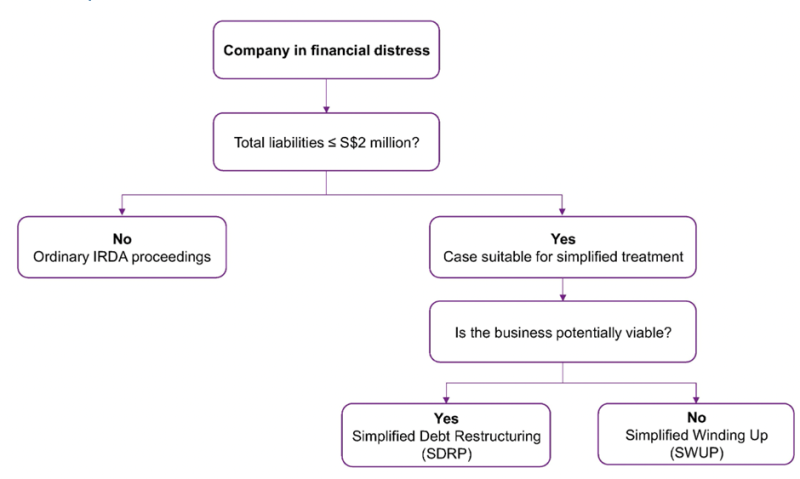

1. Eligibility: A re‑framing of what “small” means

SIP 2.0 replaces the prescriptive eligibility framework under SIP 1.0 with a single financial threshold: total liabilities (including contingent and prospective liabilities) not exceeding S$2 million.

By removing revenue, headcount, creditor‑number and asset caps, the regime reframes the concept of “small” insolvency. The inquiry is no longer whether a company fits a statutory size category, but whether the scale and complexity of the distress justify a simplified response.

This approach widens access without diluting safeguards: cases involving significant disputes, misconduct or structural complexity continue to fall outside SIP and into the ordinary IRDA processes.

2. Private‑sector gatekeeping

A further shift lies in who controls entry and conduct. SIP 2.0 places responsibility squarely on licensed private insolvency practitioners, rather than the Official Receiver, to assess suitability and administer cases.

This introduces a form of professional gatekeeping. Insolvency practitioners are expected not merely to process applications, but to exercise judgment as to whether a case properly belongs within a simplified regime, and to move it out where that assumption no longer holds.

The success of SIP 2.0 will therefore depend in no small part on the consistency and discipline with which this discretion is exercised.

3. Out‑of‑court as the default, not the exception

SIP 2.0 adopts an explicitly administrative model:

In Simplified Debt Restructuring (SDRP), creditor approval of a debt repayment plan binds all creditors without the need for court sanction, subject only to challenge on limited grounds.

In Simplified Winding Up (SWUP), liquidation proceeds without a court order, with flexibility to convert to a full liquidation if circumstances warrant.

This reflects a broader confidence in creditor voting and professional oversight as substitutes for routine judicial supervision in small cases.

4. Time as a constraint, not a buffer

One of the most consequential changes is the compression of restructuring timelines. The automatic moratorium is now limited to 30 days, extendable once (to a maximum of 60 days) only with creditor support representing two‑thirds in value.

This design assumes that viable restructurings at this scale should be capable of articulation and agreement within weeks. Where that is not possible, the regime implicitly favours a prompt transition to liquidation over prolonged uncertainty.

5. Liquidation focused on economic return

In SWUP, investigative and recovery efforts are expressly aligned with economic reality. Potential claims are pursued only where creditors are prepared to fund them; otherwise, the practitioner may proceed to an expedited conclusion and dissolution.

This acknowledges a recurring tension in small liquidations: the theoretical availability of claims does not always justify their pursuit. SIP 2.0 resolves this tension by placing the cost‑benefit decision squarely with those who stand to benefit.

A snapshot: SDRP vs SWUP

SDRP

30‑day moratorium (one extension with creditor support)

Single‑class creditor vote (2/3 in value)

No court sanction if approved

Failure triggers exit from SIP and five‑year exclusion

SWUP

No creditors’ meetings

Streamlined realisation and distribution

Investigations pursued only if creditor‑funded

Expedited dissolution where appropriate

Practical implications

For companies and directors, SIP 2.0 rewards early engagement and realistic assessment of viability. The shortened timelines leave little room for tactical delay, but provide clarity where outcomes are achievable.

For creditors, the regime prioritises speed and cost containment, while preserving targeted points of control—most notably over moratorium extensions and the funding of further investigations.

Concluding reflections

SIP 2.0 represents a maturing of Singapore’s approach to small corporate distress. By embedding a simplified regime on a permanent footing, the framework recognises that proportionality is not merely a temporary expedient, but a structural necessity in modern insolvency systems.

Whether SIP 2.0 achieves its intended objectives will turn on disciplined use by debtors, active participation by creditors, and principled gatekeeping by insolvency practitioners. If those conditions are met, the regime has the potential to deliver outcomes that are not only faster and cheaper, but also more coherent and predictable for the market as a whole.

* The article was originally published by Dentons Rodyk.